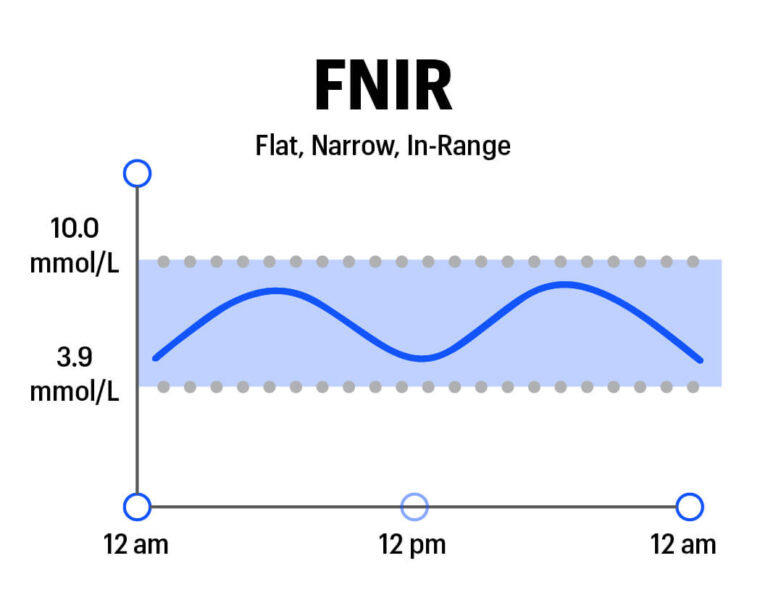

“Time in Range” (TIR) is the percentage of time that a person spends with their blood glucose levels in a target range. The range will vary depending on the person, but general guidelines suggest starting with a range of 3.9-10.0 mmml/L . (Over time or in special circumstances, some people decide to aim for a tighter range, such as 3.5-7.8 mmol/L .)

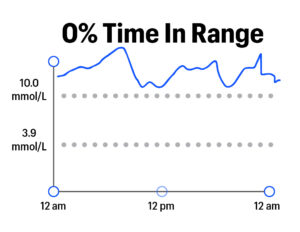

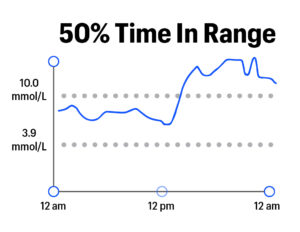

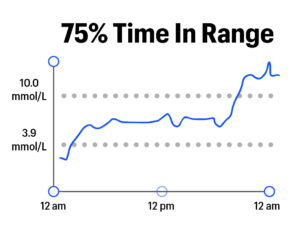

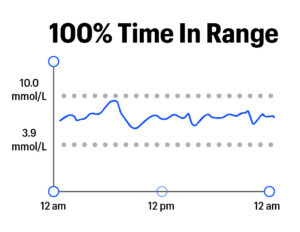

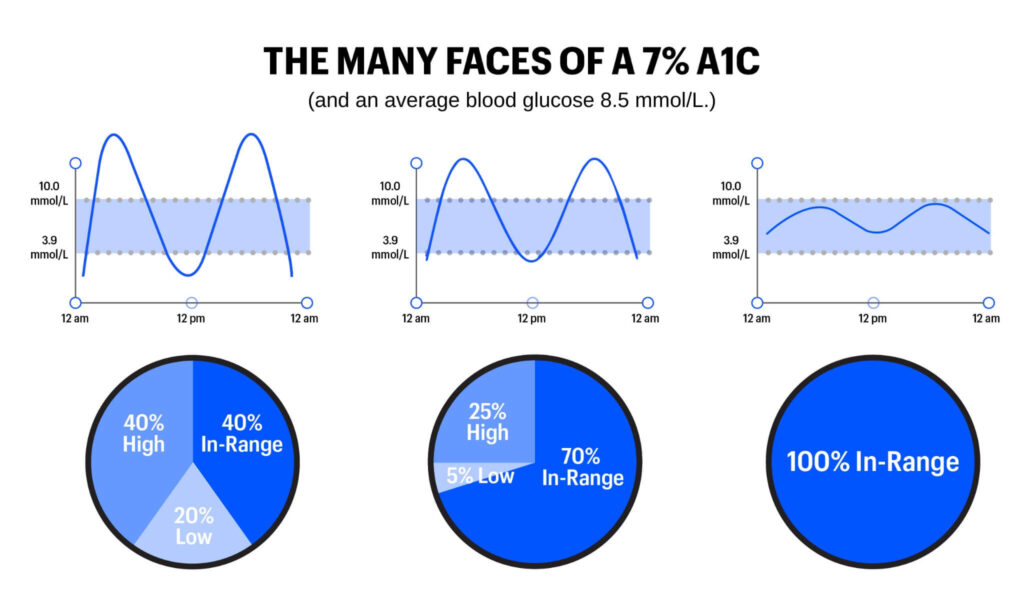

In a single number, Time in Range captures a lot about how blood glucose levels might vary throughout a day or over time. The example graphics below show various levels of Time in Range, from 0% to 100%:

TIR goes Beyond A1C in representing blood glucose levels because it captures variation – the highs, lows, and in-range values that characterize life with diabetes. By contrast, A1C is a measure of average blood sugar over a two-to-three-month period; it cannot capture time spent in various blood glucose ranges. To illustrate the limitations of A1C and the advantages of Time in Range, see the graphics below. These three examples show three different people – all with the same average blood glucose (8.5 mmol/L) and the same A1C (7%). However, the highs, lows, and in-range blood glucose values are markedly different: the first person has a rollercoaster of dangerous highs and lows, the second has moderate variability and fewer highs and lows, and the third person has little variability with all time spent in-range.

People living with diabetes experience different energy levels, moods, and overall quality of life when they are “in-range” vs. “out-of-range.” Time in Range can capture these differences in a way A1C cannot.

Because Time in Range can be measured at home on a daily basis or weekly basis (how to measure TIR), it has a huge advantage over A1C: understanding what behaviors and choices prompt more Time in Range, what drives blood glucose out-of-range, and where/when changes can be made (e.g., time of day). Thinking about blood glucose in terms of Time in Range offers a more nuanced, cause-and-effect understanding of diabetes than A1C. For instance, how do different foods affect your Time in Range? How does walking after meals affect your Time in Range? A1C cannot reveal these relationships.

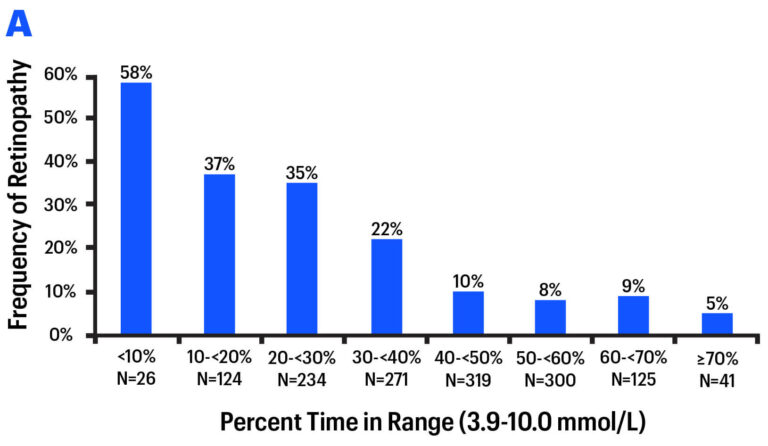

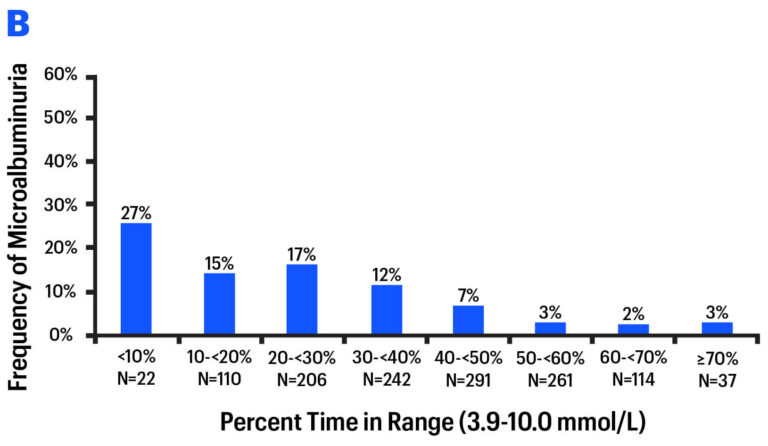

On a longer time horizon, early studies suggest Time in Range is just as good a predictor of long-term diabetes complications (e.g., Diabetes Care 2019, Diabetes Care 2018). In a re-analysis of a landmark study (DCCT), researchers found a strong relationship between different levels of Time in Range and diabetes complications: eye disease (retinopathy) and kidney disease (microalbuminuria). As Time in Range increased, complications decreased.

Some researchers believe Time in Range may emerge as a better predictor of complications, since it is a direct measure of glucose in the blood vessels – i.e., what actually does damage to the body. By contrast, A1C is an indirect measure of blood glucose, since it is dependent on red blood cell turnover.

On average, a Time in Range (3.9-10.0 mmml/L ) of 70% corresponds with an A1C of approximately 7%; a Time in Range of 50% corresponds to an A1C of approximately 8%.

It is important to speak to your health care team to establish Time in Range goals that work for you. Time in Range goals are different for every person and may depend on medication, type of diabetes, diet (especially carb intake), age, health, and risk of hypoglycemia. In general, people with diabetes should aim to spend as much time in-range as possible, taking care to avoid low blood sugars and too much burden. Experts emphasize that even a 5% change in Time in Range – for example, going from 60% to 65% – is meaningful, as that translates to one more hour per day spent in-range.

In studies and large real-world data sets, Time in Range is typically around 50% in the average person with diabetes. Recently, researchers published goals for Time in Range, above-range, and below-range for various groups of people with diabetes.

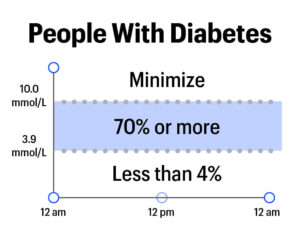

For people with type 1, experts recommend aiming for:

- At least 70% of the day in 3.9-10.0 mmol/L

- Less than 4% of the day below 3.9 mmol/L

- Minimize time each day above 10.0 mmol/L

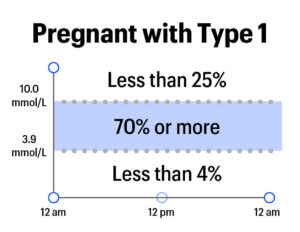

For people who are pregnant and have type 1 diabetes, experts recommend aiming for:

- At least 70% of the day in 3.5-7.8 mmol/L

- Less than 4% of the day below 3.5 mmol/L

- Less than 25% of the day above 7.8 mmol/L

What is Time in Range in people without diabetes? A recent study put CGM on people without diabetes for 10 days, finding 97% time-in-tight-range (3.9-10.0 mmol/L), with blood glucose levels averaging 5.5 mmol/L and showing little variation.

To determine your TIR, you should use at least 14 days’ worth of blood glucose data.

TIR is most accurately measured using a continuous glucose meter (CGM), although a blood glucose meter can also be used.

CGM provides a constant stream of information about your blood sugar – every five minutes – which means that you have a full picture of precisely how many hours of the day you spent in your target range. This includes overnight and after meals, which are usually missed with fingersticks.

If you have CGM, TIR is calculated automatically in the software/app that comes with your device: Dexcom CLARITY Mobile app and CLARITY on the computer; FreeStyle LibreLink mobile app and LibreView on the web; and Medtronic’s CareLink on the web.

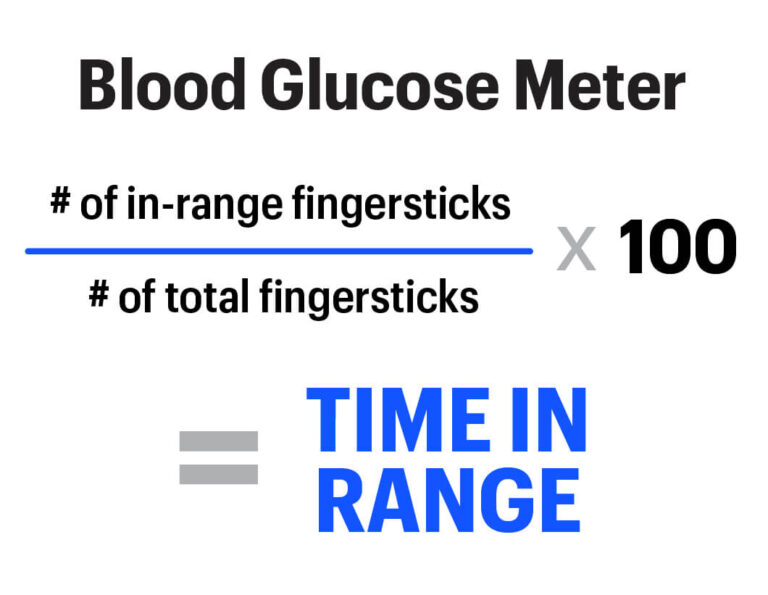

With a blood glucose monitor, the more fingersticks you take throughout the day, the better the picture you’ll get of your TIR. Make sure to get readings over at least two weeks, ideally with some fingersticks taken after meals and overnight.

If you are using blood glucose monitor data, TIR is the percentage of your data points that fall in your range over a period of time. You can most easily calculate TIR with an app, by entering or uploading your blood glucose monitor fingerstick data. If you don’t have a monitor with Bluetooth, you can take 14 days of fingerstick data and calculate TIR manually using this equation:

Please speak to your health care provider to learn more about the best option for you to measure Time in Range.

- Talk to your diabetes care team

- Wear CGM or check blood glucose more often, using the data to understand patterns

- Minimize the biggest glucose disturbances and sources of error

- Make course corrections when out-of-range blood sugars occur

- Focus on habits vs Time in Range %

- Watch and learn about your trends (ex. High BG after dinner? Low BG before lunch?)

- Make one change at a time and see if Time in Range improves

For more information about Time in Range check out our Let’s Talk Education presentation by clicking on the link here. https://youtu.be/WFwmL9UWDPg

Scientific Papers

Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range in Diabetes Care, August 2019

Validation of Time in Range as an Outcome Measure for Diabetes Clinical Trials in Diabetes Care, March 2019

Association of Time in Range, as Assessed by Continuous Glucose Monitoring, With Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetes in Diabetes Care, November 2018

The Fallacy of Average: How Using HbA1C Alone to Assess Glycemic Control Can Be Misleading in Diabetes Care, August 2017

The Relationship of Hemoglobin A1C to Time in Range in Patients with Diabetes in Diabetes Technology & Therapuetics, February 2019

Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, Amiel SA, Beck R, Biester T, Bosi E, Buckingham BA, Cefalu WT, Close KL, Cobelli C. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diab Care. 2019;1(42):1593–603.

This page is made possible by support from the Time in Range Coalition. The diaTribe Foundation retains strict editorial independence for all content.