In addition to funding critical type 1 diabetes (T1D) clinical trials, a key focus for JDRF is increasing awareness of and participation in trials. All new interventions, from drugs to devices to programs like mental health and peer support, must undergo clinical trials before they can be applied in everyday practice and benefit the people who need them most. By facilitating progress in clinical trials, JDRF is helping to ensure that the most promising T1D research advances can make a difference for anyone affected by the disease. asdfsdf

We know that many clinical trials fail due to low participation — simply because potential participants didn’t know about them. Over 80% of JDRF-funded trials are delayed due to low participation. There can be many reasons for this, lack of information about what’s involved in a clinical trial, or concerns about risks. Below are answers to some key questions we hear from our community – as well as some of the important benefits that many research participants experience.

What is a clinical trial:

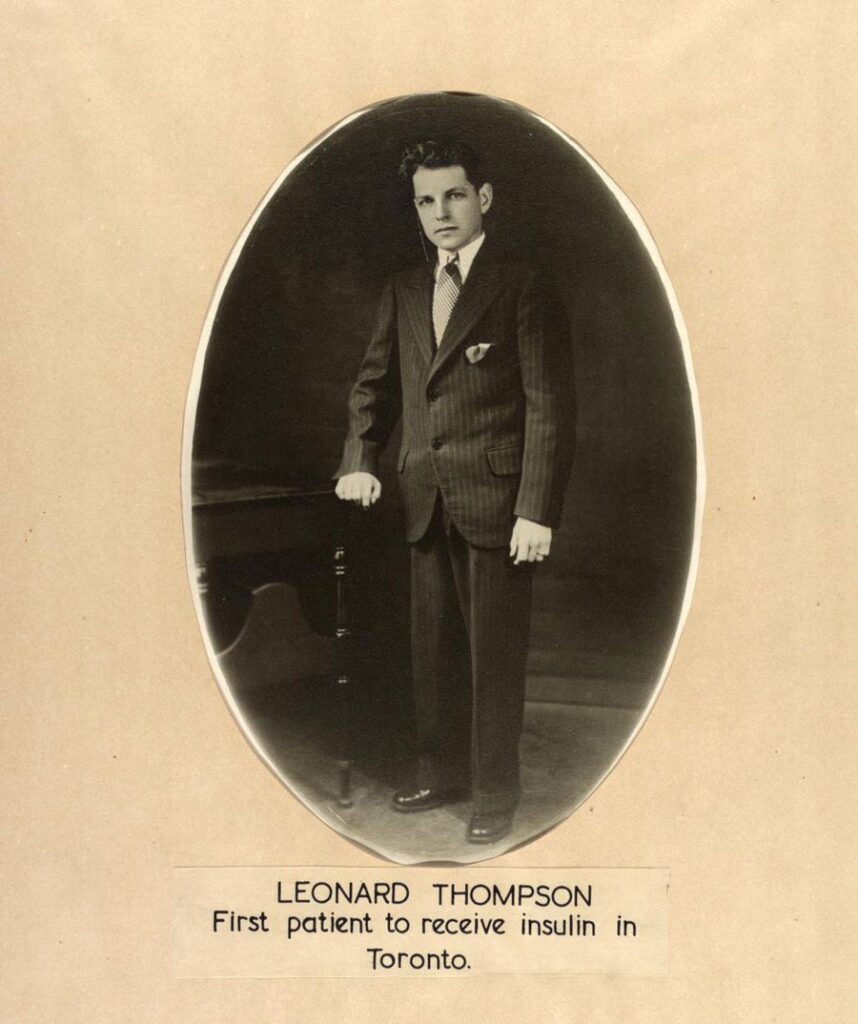

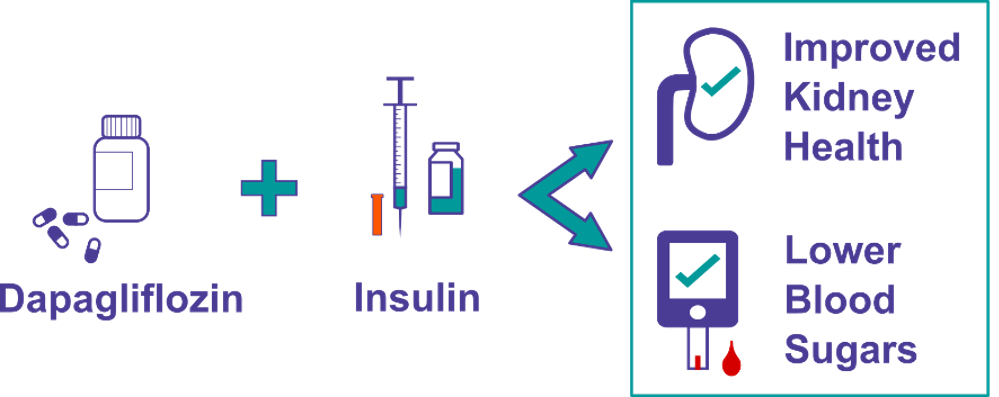

Almost any new test, treatment, device, or program that will become part of clinical practice, must first undergo clinical trials. This can include drugs (such as types of insulin), devices (such as insulin pumps), virtual care platforms (such as digital health apps), behavioural therapy (such as peer support), education programs (such as diabetes awareness programs), exercise and diet programs (such as high intensity exercise regimens), and many more. The purpose of clinical trials is to determine the safety (including possible side effects) and efficacy (how well the intervention produces the expected response) of the intervention.

This is a general overview of clinical trial phases for development of a new drug:

What is it like to participate in a clinical trial?

Participating in a clinical trial can be a daunting prospect for many people. It involves undergoing a new treatment or therapy that has not yet been fully tested for T1D, which can understandably cause fear and uncertainty. Additionally, there may be logistical, financial, or personal barriers that prevent individuals from participating in clinical trials. However, these factors vary widely across trials, as some are minimally invasive (e.g., signing up for a registry), entirely virtual (e.g., a mental health app), or even look at improving upon a known beneficial intervention (e.g., a new physical activity regimen). Trials can vary from virtual involvement of only a few hours, to surgical procedures with year(s) of follow-up, and everything in between.

One of the most significant fears someone may have about participating in clinical trials is the fear of the unknown. Many people are nervous about trying a new treatment or therapy that has not yet been fully tested. They may worry about potential side effects or long-term risks of the treatment. Or that the treatment may adversely impact their current T1D management. However, it is essential to remember that clinical trials are designed to be as safe as possible, and all interventions undergo rigorous ethical approval and, for drugs and devices, Health Canada approval before being offered to participants.

Another fear individuals may have about participating in clinical trials is the fear of losing control over their healthcare decisions. They may worry that they will not be able to make their own decisions about their care or that they will be pressured into participating in a trial. However, all clinical trials are voluntary, and individuals can choose to withdraw from a trial at any time if they are not comfortable.

Logistical barriers can also prevent individuals from participating in clinical trials. For example, clinical trials may take place in a different city or province, which can make it challenging for some to attend appointments. Additionally, some trials may require participants to take time off work or arrange childcare, which can be difficult for some people. However, many trials have a travel budget to bring participants in from other cities or provinces at no cost to the participant, and research teams tend to make efforts to work around participants’ schedules, where possible.

Finally, concerns about financial barriers can prevent individuals from pursuing participation in clinical trials. However, many clinical trials offer compensation for participants, which can cover, or offset costs related to travel or taking time away from work, school, or childcare. Potential participants are informed about this upfront before agreeing to participate in the trial.

What is a placebo?

Many people are concerned that they will be in the placebo group of a clinical trial and will invest time and energy to not receive any benefits. While this is a very valid concern, there are still major benefits to being in a placebo group:

- All participation is valuable: even being in a placebo group helps contribute to a cure or advancement in T1D research and resources.

- Added care: participants in placebo groups still benefit from the added healthcare that is standard in a clinical trial. This may be especially beneficial for people with T1D who don’t have routine access to endocrinologists / medical teams for any reason (such as living in a more rural area).

- Compensation/access: if trials have a budget to compensate participants for their involvement, everyone will be compensated equally, regardless of group (placebo vs. intervention) assignment. In addition, if the intervention is successful, participants in the placebo group may have first access to it following the trial.

There are different ‘types’ of placebos for clinical trials; not all placebo groups receive a ‘sugar pill’:

- Intervention vs Nothing (sugar pill): this is used when the intervention is new enough that there isn’t any existing therapy to compare it to. For example, in clinical trials of teplizumab, the drug was compared to a ‘sugar pill’ since no other disease-modifying therapy existed to compare it to.

- Intervention vs Standard of Care: this is used when there is an existing, similar therapy available. The new intervention will be compared to the existing standard of care to determine if its efficacy is equal to, or better than, what already exists. For example, new insulin pumps or CGMs may be compared to existing models, or a new type of insulin may be compared to an insulin already on the market.

- Crossover Design: this design is frequently used for devices, behavioural, exercise, education, or mental health interventions. One group will receive the intervention for a period of time, while the ‘placebo group’ is placed on a waitlist and monitored/surveyed without any intervention. After a set time, the groups will switch and the ‘placebo group’ will receive the intervention while the first group is followed for a period of time without the intervention. Everyone in the study receives the intervention, and researchers get an extended period of tracking the efficacy of the intervention.

What is informed consent?

All clinical trials start with an informed consent document. This document will outline everything about the research, including all the procedures, visits, potential side effects, supports in place, etc. It is the responsibility of the research team to walk you through this document and answer any questions that you may have.

This document will also indicate the ethical approval steps that the study has undergone (typically through a university or hospital research ethics board). Information will also be given as to how you can report any adverse side effects, how you can leave the study at any time, and how you can contact the research ethics board if you have any concerns.

It’s important to note that consent to participate in research must be free, informed, and ongoing. This means that consent is given voluntarily, that the potential participant fully understands the purpose of the research, their involvement, the risks, and benefits, and that consent is ongoing from the beginning to the end of the study. Please note that an informed consent document is not a legally binding document, and participants can withdraw from a study at any point in time without penalty.

What is an observational clinical trial?

Clinical trials do not always require an intervention being given to the participant. There are also observational research trials where the research team is recording something from the participant without giving them anything. Examples of this may be T1D screening (such as TrialNet, where the research team is taking and testing blood samples to determine risk of T1D), follow up studies from previous trials (such as teplizumab follow-ups which are tracking the initial participant group for a number of years), or disease registries (such as BETTER, where the research team is recording information about Canadians who live with T1D so that all researchers in Canada can have a better understanding of the T1D population).

If you are interested in participating in research but don’t know if you are prepared to receive an intervention, please consider taking part in an observational trial such as the BETTER registry. This is open to all Canadians with T1D (persons 14 and over sign up for themselves, parents/caregivers sign up on behalf of persons 13 and younger with T1D).

Where can I find out more information about T1D trials?

- JDRF.ca Clinical Trial page

- Impact newsletter sign-up

- Clinicaltrials.gov

- Research@jdrf.ca

- Antidote tool

How else can I get involved?

To help ensure that JDRF’s Clinical Trials Education Program is aligned with the needs of the T1D community, we will grow and engage an existing group of volunteers with lived experience of T1D who advise on our research programs. Through the Clinical Trials Education Program, these Research Collaboration Volunteers will have the opportunity to share their diverse experiences and perspectives with research teams to influence the design and execution of clinical trials and other research studies.

Although not essential, we are particularly interested in engaging people with lived experience of T1D (either as a researcher in any field, a past participant in research studies, or any other significant exposure to research).

This crucial group of volunteers will promote diversity in T1D research, ensure that the participant voice consistently informs research, and help to accelerate the translation of knowledge between researchers, the T1D community and other stakeholders.

Please email research@JDRF.ca to learn more or express your interest.

Support JDRF’s Clinical Trials Education Program: please email jbavli@jdrf.ca