I’ve lived in Toronto my entire life. I’m currently 60 years old, I was diagnosed in 1970, 53 years ago. I remember getting up in the middle of the night, needing juice because I was so thirsty, I was going to the washroom all the time. I remember being diagnosed, going to the hospital for over two weeks. I went to the hospital from one house, came home to a new house, because my family moved while I was in the hospital.

Can you share what T1D management was like 50 years ago?

It certainly was different. Everything was very regimented. My mother had to weigh all the food I ate. I still remember the scale that measured the food I could eat. You based how much food you ate on the set amount of insulin that you were given once a day.

I started off with a glass syringe that had to be sterilized every night. One needle in the morning, and urine testing, you didn’t really know what your blood glucose level was.

The first change was multiple injections, a basal dose of insulin that lasted 24 hours in theory, and then you would take a shot before every meal, a faster acting insulin. That was the real big change for me, well before insulin pumps were available to the public. Medtronic was working on developing a pump around the same time. The next big change in management was the at-home blood glucose test, but you could still only check it at home (couldn’t take it with you to check anywhere else). It was big and bulky, like a VHS tape.

At least you knew what your blood glucose levels were, and then we moved into much more accurate testing, which allowed us to adjust our insulin. The early 80s was when that all started to change.

What innovation or research update has excited you the most as someone living with T1D?

Companies like Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly who started to develop newer insulins, as opposed to the beginning when it was just one time a day and it was a bovine/porcine derivative. This was more pharma research than clinical research.

The research that JDRF was funding at the time was cure-based and scientific, very different from today’s type of research. There were all types of researchers working on complications in those days as there were so many more people that experienced T1D-related complications. The research world after the discovery of insulin became about mitigating the complications as everyone in the 40s, 50s, 60s all had complications from the disease.

When JDRF was founded in 1970 in the US, and Canada in 1974, that is what really pushed the needle forward (in T1D research).

What was it like as the child of one of JDRF Canada’s founding families?

I was diagnosed in 1970, at seven-years-old, and my parents were very progressive people, not a sit around and wait for things type of people. Immediately they went to a CDA (Canadian Diabetes Association) meeting, and they were told how to use diet and exercise to help people live better with diabetes.

My mother put up her hand and said, ‘what about a cure for people’? She asked the chairman about research. He said, ‘that’s what the government does’, and she left the meeting crying.

Soon after, she got connected to the Garfinkle family who had just started a (JDRF) chapter in Montreal. She dug into her American roots and connected with the Lurie family in NYC (who had helped to start JDRF International), and she and my father spent a lot of time and energy and worked on becoming the first affiliate of JDRF.

My mother’s full-time job was JDRF after that. She volunteered her entire life. My father was heavily involved as well.

I also spent most of my life involved with JDRF in some way or another. I got involved in the Rolls Royce Raffle as a teen. I felt like I should volunteer too, knowing that my parents were working so tirelessly for me. The Walk and then Ride came along, and I was on the Toronto chapter board, and then the Toronto chapter Chair for a while.

Years went by, I went to school, got married, and got involved in JDRF International (JDRFI) too. I always felt it was my responsibility to give back and continue my parents’ legacy, as this was my disease. I’ve sat on both the Canadian Board, and the International Board. Nobody else has the history that I do. I do one-year renewals on the JDRF Canada Board, if they say it’s time for me to leave, it won’t do anything to change my involvement. I also sit on the International Global Mission Board, I say it’s my second full-time job.

What has the support of donors and volunteers allowed JDRF to accomplish?

We are a volunteer-staff partnership organization like no other. Most charities are staff-led, and volunteer supported. JDRF from day one was volunteer-led. The first office was in the basement of our house. It was all volunteers. Eventually, they felt we were raising enough money to hire one staff member. But without the volunteers, there would be no organization. We couldn’t do what we do without them.

How is JDRF there for those impacted by T1D?

Tremendously, in a nutshell. If there was no JDRF, there would be no hybrid-closed loop system on the market. It wouldn’t exist. I was on the International Board when that was brought up, we were at a tipping point. When I first came on the Board, most of the research we funded was cure-based, lab-based research. We had never funded companies that were going to produce products. But our Board then said, ‘maybe it’s time. Maybe it’s time we invest in these companies coming to us looking for funding for devices, innovations and technology’.

We took some of our research funds and said we would invest in Dexcom (out of California). It was very contentious, there were some heated discussions, Aaron Kowalski (who also has T1D) who was head of the JDRFI Research Department, and it was approved. Dick Allen was a grandparent of a child with T1D, went to get a pump for his grandchild, and he put a group together and he created Tandem. And with Dexcom that got us to the closed-loop system.

For me personally, it (the hybrid closed-loop system) was a lifesaver. I have hypoglycemic unawareness. I’d be riding on my bike and my blood glucose would drop below 2 and I had no idea. It’s improved my quality of life in tremendous ways.

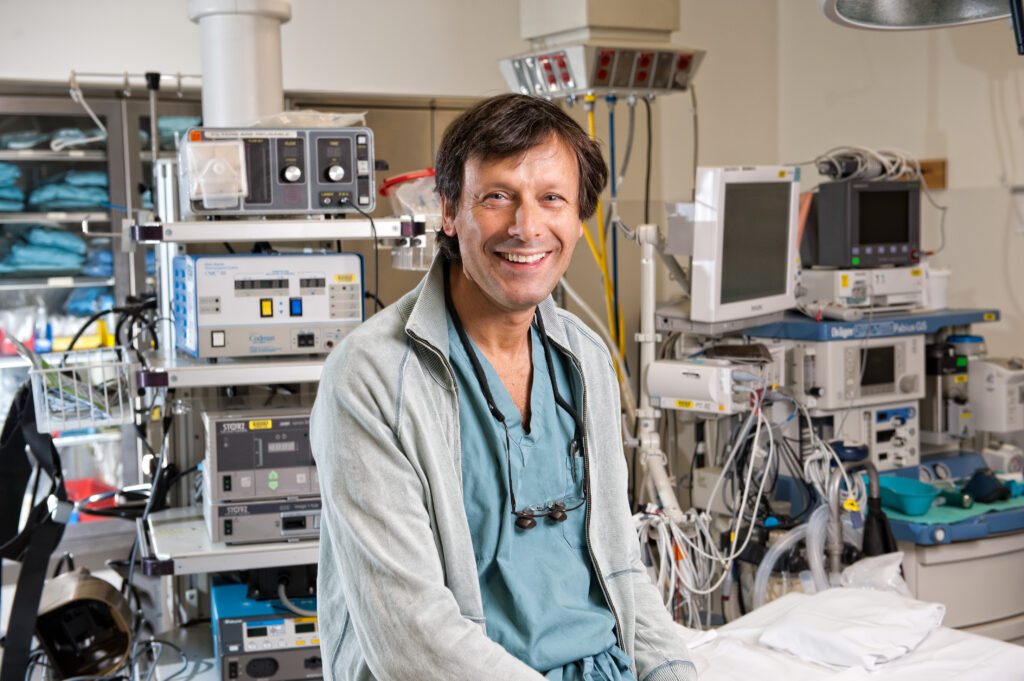

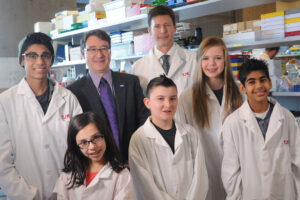

And here in Canada, we still haven’t strayed from our cure-based research roots. The Edmonton Protocol, discovered by Dr. James Shapiro was funded by JDRF, and we are still funding stem-cell based research.

I myself am willing to be part of the gene-edited Vertex study to see if stem-cell transplant could work as a function cure for me.

What would a cure mean to you?

To me, the $100 million question is what an ‘actual’ cure is. It will be a phased approach. It won’t be overnight; I won’t wake up and no longer have T1D.

I already have the first step of that cure. That’s the closed-loop system. The ultimate cure, stem-cell replacement for those of who live with it, another functional cure is something like T-Zield, taking a shot that stops you from going to phase 1 to phase 3 of T1D. Screening and prevention. In the future, maybe through vaccinations. They’ll be able to narrow down what causes the autoimmune attack and stop it from happening. And I am 100% confident that will happen. And that’s something I say having been both involved with JDRF and living with T1D for over 50 years. We are in exciting times.